An Excerpt from Fearless as Possible (Under the Circumstances)

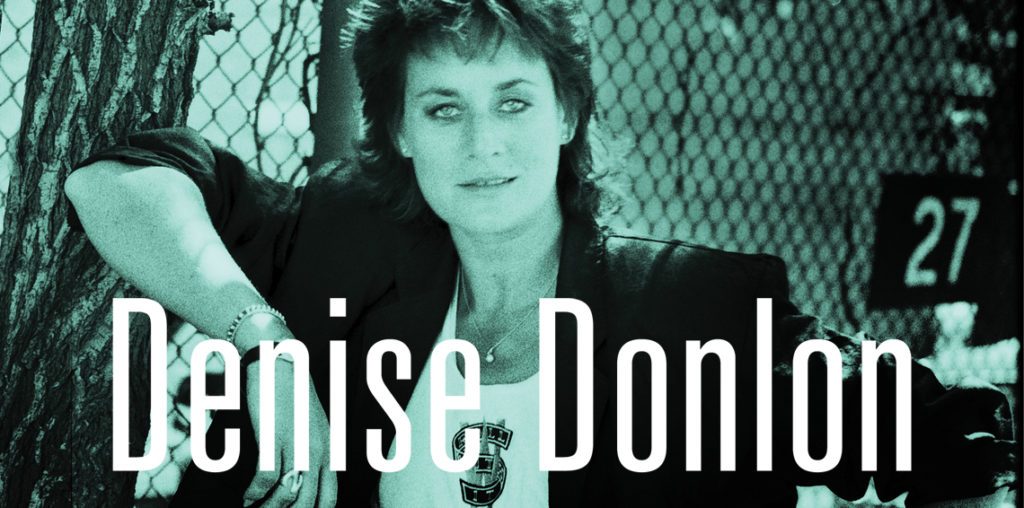

Feminist. Social Activist. Broadcaster. Corporate leader. One of Canada’s most celebrated and dynamic citizens, Denise Donlon has long been recognized as a trailblazer in the Canadian cultural industries.

The following is an excerpt from Denise Donlon’s new memoir Fearless as Possible (Under the Circumstances), forthcoming from House of Anansi on November 5, 2016. This excerpt appears in chapter 16, “Welcome to Sony, the Honeymoon is Over.”

Welcome to Sony, the Honeymoon is Over

Little did I know, when I joined Sony Music Canada in December of 2000, that I was walking into an industry-wide meltdown. The business had been circling the bowl for some months at that point, but few saw the sky falling. After all, the previous year had been brilliant. Worldwide sales in 1999 had reached $38.7 billion U.S. — the highest ever in the recording industry. Turns out, that was the peak. It was downhill from there. My timing could not have been worse.

I’d never worked at a record company, let alone been the president of one, and my learning curve was so steep it was vertical. According to my daytimer, in the first two weeks I analyzed the budget; addressed the troops; found the washroom; reviewed the artist roster; met with HR; responded to dozens of “welcome to the company” calls from fellow international Sony execs and artist managers calling to wish me well, complain about the past, then ask for something; got up to speed on Celine Dion’s Vegas plans; vowed to halt cross-border imports; studied the vagaries of Quebec sales; found trust in finance and business affairs; joined an industry pitch to CTV for a Canadian chart show; approved a Ricky Martin promo budget; travelled the depths of the manufacturing warehouse; tried to memorize the list of distributed labels; scrutinized the release schedule; and endeavoured to make heads or tails out of a tutorial I received from my (departing!) CFO on standard artist payment structure.

The first few days for a CEO are precisely when you must get control of your calendar. Everything from long-ignored HR issues to obscure operations matters will attempt to storm the schedule. Strike while the iron’s hot, they’ll say. Get her while the door is still open. If you’re not careful, you could be hit by the shrapnel of past skirmishes and pressed into service on unresolved issues such as:

- – Can employees bring their dogs to work? (Yes. But check if there’s someone who’s allergic.)

– Should we use more environmentally friendly pesticides on the company lawn? (Sure!)

– Should we open an in-house daycare? (No. What happens when strategic marketing’s kid bites health and safety’s little darling?)

Business gurus will tell you that great leadership means being able to see the big picture, to clearly communicate the goal, and then to motivate the hearts and minds of those in your organization so they’ll follow you over the hill to victory. “Hire and Inspire!” they say. They also say, “Don’t sweat the small stuff.” But what happens when the landscape is so new that everything seems consequential? When it’s so new that you suspect a devil in every unfamiliar detail?

At Much, I’d been at a point where I no longer sweated the small stuff, which left me time to focus on the big stuff like the bomb threat when Madonna visited or the ever-amusing regulatory undertakings. And because I’d come up through the ranks, I could trust my gut. On difficult calls I was seldom challenged.

Sony was very different. Instead of reporting to a family-owned company, I was a cog in a large multinational corporation with so much company jargon that it seemed like a new language. But I soon figured out what bisphenol polycarbonate was (it’s the hot goop CDs are made of), how Six Sigma worked (it’s a quality-control and efficiencies-measurement system), and what the sales department meant when they talked about “shrinkage.” Turns out it’s less about cold-water swimming and more about product theft at the store level.

Luckily, when it comes to leadership skills, most gals come well equipped. Anyone who has CEO’d a household knows what it means to organize, prioritize, and energize a team. Women with children excel at motivation and multi-tasking, and I dare say that without a sense of humour mothers would require medication. And moms know that even when you’re in charge it’s okay to ask questions — people are delighted to impress you with their knowledge at the playground and at work.

For me, the old “fake it ’til you make it” has never worked. The only way I’ve built any confidence is hour by hour, just like Thomas Edison said: 99 percent perspiration, 1 percent inspiration. And, as a woman, I’m sorry to say, you do need to run faster, work harder, jump higher, and learn to thrive sleep-deprived. Remember what was said of Ginger Rogers: “She did everything Fred Astaire did, backwards and in high heels.”

There’s an early moment of grace in any new job. In those first few days, you actually have time to attend all the departmental meetings and get a sense of what’s going on. But when you’re in a leadership role, that moment is over quickly. You then have to make some strategic decisions about what your priorities will be, and likely some “blink” judgements on the people you decide to relieve or retain. You can’t do any of that well if your calendar is crowded. You must be disciplined about delegation, make time for your own creative thinking, and fiercely control your schedule (one day I may even manage to take my own advice).

Roosevelt’s first-100-days approach is now widely accepted as the timeline for establishing new leadership. The company wants inspiration. Walk in with your speech already written. Clearly communicate your vision, set measurable goals, then go get ’em. Attack the priorities, demonstrate some early wins and dig in hard during those next ninety-nine days.

That was my intention, but as John Lennon wrote: “Life is what happens to you when you’re busy making other plans.”

I was ten working days in when my world flipped upside down. It was a week before Christmas, and I was on the phone with Stu Bondell, head of international business affairs at the New York office. The call was intended to brief me on our various international contracts and build a game plan for addressing outstanding issues. Stu is one of the smartest and, turns out, kindest guys in the business. I’d been nervous about the call, fully expecting to be overwhelmed by legalese, but I had Ian MacKay with me, head of business affairs in Canada, who, along with my new head of finance, Karl Percy, soon became a trusted ally and friend.

We were only a few minutes into the conversation when the front desk interrupted.

“You have a call from a hospital,” she said.

I knew Murray was in for an angiogram. I had been expecting a call from him, telling me what time he might be done so I could pick him up.

“That will be Murray. Can you let him know I’ll be there in an hour?”

“Okay.”

A moment later she buzzed again. “Sorry, they said it was urgent. I tried to get a number for you to call back, but they are insisting they talk to you.”

“Okay. Sorry, Stu, could you hold for a moment?”

I picked up the other line and heard the words: “Your husband has had a cardiac episode. We’re preparing an emergency surgical team.”

I can’t remember much more of what was said. Stu and Ian continued the call as I raced to the hospital. On the way I called my mom to pick up Duncan, then called Calvin, Murray’s brother, to meet me there.

Within the hour, Murray’s immediate family was assembled in the waiting room: his two brothers Calvin and Bill, his sister Sandy, and me. The doctor told us Murray was undergoing open-heart surgery. It seemed impossible. He’d gone straight to the hospital from a karate class, where he was working on his second-degree black belt. He was in strong physical shape. He’d gone off in a great mood.

This was supposed to be routine — “Nothing to worry about, just a simple procedure.” Murray’s doctor had sent him in largely because Murray was a pilot. In order for pilots to retain their licenses, they are subject to more rigorous medical examinations than the rest of us, and rightly so — you don’t want your captain clutching his chest at 10,000 feet.

Around 11 p.m., the heart surgeon walked into the waiting room.

R. J. Cusimano is an impressive man — a top-gun cardiovascular surgeon who the nurse had referred to as “The guy who does all the geriatric triples.” He was about to go off shift, but had been called to consult on Murray’s incident and decided that he’d stay to do the operation himself.

He walked into the waiting room and told us Murray was in ICU, and that the surgery had gone well. Then he asked, “Family?” We all nodded, identifying ourselves as wife, brother, sister, brother. His focus turned to Sandy, Bill, and Calvin.

“Any history of heart disease in your family?”

“No,” they all said.

“There is now,” he said. “You should all get a stress test as soon as you can.”

An hour later we were allowed to see Murray. It was a gruesome sight: tubes in his neck and along his arm and a big ventilator in his mouth, mechanically blowing air — up and down, up and down — into his chest. Cusimano had done a quadruple bypass. He said he only really needed to do one, but once he was in there, he thought he’d “zero time” him. I had always thought that the distinctions of double bypass, triple bypass, and quadruple bypass indicated an increasing severity of the operation, but evidently it’s the opening of the chest and the fiddling with the heart that constitute the big stuff. Once you’re in, adding another bypass or two is apparently no big deal.

Once we’d looked in on Murray, we stepped outside and were confronted by a wall of freezing rain. Calvin took out a cigarette and handed me one.

“Stress test?” he offered.

Calvin’s droll humour. So perfect. I took it.

By the next day, Murray was off the ventilator but was still in ICU. No visitors were allowed except me. I’d called everyone I could think of that would want to know. I wasn’t getting a whole lot of answers from the nursing staff, but didn’t really know what questions to ask. I was focused on how he was doing, how long it would take to heal, what procedures to follow once he came home.

By day two, December 23, Murray was in the cardiac ward with three other heart patients, all much older than he was. He’d had a busy morning: he’d shuffled halfway to the nurses’ station and back before I got there. They want to get heart patients up and walking as soon as they can. Dr. Cusimano swung by, all chipper and full of encouragement. I couldn’t stop looking at the surgeon’s hands. Those hands had been inside Murray’s chest, holding and repairing his actual heart.

Murray was looking better and many of the tubes had been removed. He was blowing into a something called an incentive spirometer, making a ball hover with his breath. Duncan came with me and seemed to handle it all pretty well. Once he was satisfied that he could still give his father a hug, he focused his attention on the beeping machines in the room and then the vending machines down the hall.

As soon as Murray could receive guests, they arrived. Tom Cochrane, Ian Thomas, and Marc Jordan tumbled into the room, guitars in hand and Santa hats on their heads. They sat at the foot of Murray’s bed and played and sang.

It was surreal to hear human voices harmonizing in that harsh environment. The guitar sounds echoed off the linoleum floors and swam around the green-washed room, siren songs capturing the attention of everyone on the floor — “What the hell . . . ? Where’s that coming from? What’s going on?” Nurses stuck their heads in; visitors stood stock-still in the corridors; heart patients staggered toward the room pushing their walkers and dragging their IVs, gawking through the door while their backsides hung out in the hall.

Christmas music. Just a few sweet songs. A warm human gift to remind us that even damaged, cranky hearts can be mended and beat strongly again, full to burstin’ with tenderness, friendship, and love.

In a few days Murray was home, with his pills, his post-op instructions, and his red heart-shaped pillow. He was different. He was as weak as a baby but mentally he was ablaze, full of wonder and appreciation, like a kid discovering a shiny stone on the beach. I used to joke that Dr. Cusimano must have fixed the part of his heart that returned phone calls.

As Murray healed, the real story about what happened started to come out. His cardiac trauma had been caused by the procedure. The term is “iatrogenic” — a condition caused by interaction with a physician.

It turns out Murray has a left-sided heart. Apparently this is true of about 10 percent of the population, and it means that instead of the coronary artery splitting two ways, left and right, it goes only one way. Murray’s angiogram had been conducted in a teaching hospital, and the person who was doing the procedure had tried to force the catheter the wrong way; in doing so, he’d torn the lining of Murray’s coronary artery, causing an enormous blood clot to form. That would have killed him had they not gone in.

So Murray didn’t have a heart attack. It was a routine procedure that went very wrong.

Murray decided to have a frank conversation with his original doctor. If he levelled with him, Murray would accept what had happened as an accident and move on. Which is what happened and what he did.

Deciding to forgive like that would have been a big decision for anybody, but I think doubly so for an artist. An artistic life is insecure — for many, it’s a hardscrabble existence: hand to mouth, feast and famine. There are no pension plans, no medical and dental. A big financial windfall would make any artist’s life easier. But Murray chose to act with integrity. He’s a man who thinks of principle before money, of honour over opportunity, and that’s just one of the reasons I love him.

At the time of Murray’s heart incident, he had been writing, recording, and performing for thirty-seven highly successful years. He had twelve Juno awards, three gold records, and his work had been covered by artists like Waylon Jennings and Kris Kristofferson, recorded by Tom Rush and Melanie. His honours — including an Order of Canada — are too many to mention, but above it all he is a terrific father and loving husband and I was so very grateful we didn’t lose him.

The first days at Sony had been a whirlwind for sure, but having Murray home from the hospital and recovering well put everything in perspective. The brush with death made our bond stronger, and we knew we could count on each other “in sickness and in health.” And I was lucky to have Murray for support. Because life at the new company was about to get truly hairy.

Feminist. Social Activist. Broadcaster. Corporate leader. One of Canada’s most celebrated and dynamic citizens, Denise Donlon has long been recognized as a trailblazer in the Canadian cultural industries.

Feminist. Social Activist. Broadcaster. Corporate leader. One of Canada’s most celebrated and dynamic citizens, Denise Donlon has long been recognized as a trailblazer in the Canadian cultural industries.

In this smart, funny, and inspiring memoir, Donlon chronicles her impressive and storied career, which has put her at the forefront of the massive changes in the music industry and media. From her early days at MuchMusic and the cult show The NewMusic, where she was a host and producer, she quickly moved up the ranks as director of music programming and VP and general manager. Her mandate was relevance, during a time when music videos became a medium that would change pop music and popular culture forever. She became the first female president of Sony Music Canada, where she navigated the biggest crisis in the music industry with the rise of Napster and the new digital revolution. She then joined CBC English Radio as General Manager and Executive Director when the corporation absorbed cutbacks on federal funding, leading to mass layoffs, the closure of stations, and a shadow over the future of Canada’s national public broadcaster.

Throughout her incredible journey, she shares colourful and entertaining stories of growing up tall, flat, and bullied in east Scarborough; interviewing musical icons such as Keith Richards, Run-DMC, Ice-T, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Annie Lennox, and Sting; working with talent agent Sam Feldman, media pioneer Moses Znaimer, executive vice-president of CBC Radio Richard Stursberg, and her co-host on the current affairs magazine show TheZoomer, Conrad Black. And finally, she details her life-changing experiences with WarChild Canada and her work with other charitable organizations, including Live8 and the Clinton Foundation.

Told with humour and honesty, As Fearless as Possible (Under the Circumstances) is a candid memoir of one woman’s journey, navigating corporate culture with integrity, responsibility, and an irrepressible passion to be a force for good.