"This Pride, let us recommit to sex work solidarity" by Marcus McCann

Written by Marcus McCann, author of Park Cruising

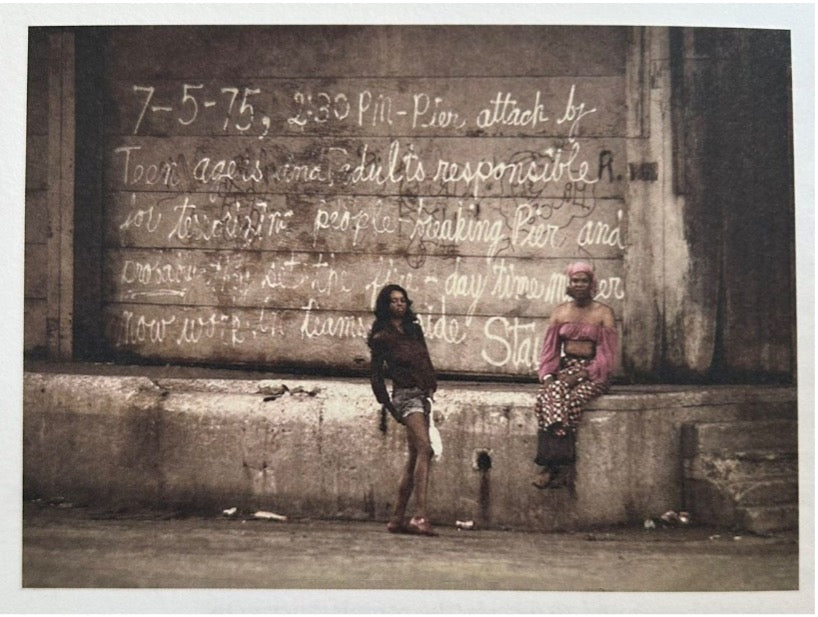

There is a vein of writing about cruising that marks it out as a masculinist project, a utopia without women. Such writing makes me uncomfortable, in part because I keep thinking about Shelley Seccombe’s photo, Newspaper Wall, West Street, 1975.

The photo was taken at the entrance to the piers in New York which, in 1975, was a neglected and crumbling corner of the city. The spot became a site where men went to meet each other for sexual encounters which were anonymous and fleeting. It was also a place of intense socializing. There are photographs of dozens and sometimes hundreds of men sunbathing together there in cutoff shorts or completely naked on summer days in the 1970s. And it is for these aspects of gay men’s social and sexual lives that the piers in the period are most remembered. But the piers were also a space where trans women—although we were just starting to use the term “transgender”—would gather and socialize. Without making assumptions, the pair in Seccombe’s photo were part of the pier scene, and they looked fabulous.

Newspaper Wall, West Street, 1975, Shelley Seccombe.

On the other side of the country, in Los Angeles, John Rechy recounts stories of gay men’s pre-Stonewall street cruising. These sidewalks and parks were populated not just with gay men, but also queens and fairies wearing women’s clothes. The queens often turned tricks, and they’re hardly alone in doing so.

Johnny Rio, one of Rechy’s iconic heroes, has an ambivalent relationship to hustling. On the one hand, he does pick up strangers for unpaid sexual encounters if they pass his exacting standards of beauty and masculinity and are prepared to engage in non-reciprocated one-way oral sex. But most of Rio’s tricks pay him for sex. Rechy’s characters do both of these things from the same urban locations—sometimes only deciding whether to ask for money partway through an encounter.

Cruising and hustling are intimately bound up, but the connection is rarely discussed. John Preston, for example, describes taking public transit downtown to trick with travelling salesmen in Boston as a teen, circa 1960. He was excited about the sex, not the money, and at first, he tried to refuse offers of payment. The money was a problem: he worried that it would lead his parents to ask unwanted questions when he got home. How could he tell them where the money was coming from? Since his would-be suitors insisted on paying, he devised a solution. He put the cash into an envelope at the end of the night and sent it to a museum or art gallery, without a return address.

Trans identities and sex work—or assumptions about sex work—are also historically connected. This is well illustrated in Antonio Giménez-Rico’s 1983 Spanish documentary Vestida de Azul. In that film, the six main characters have an almost kaleidoscopic set of overlapping and contradictory attitudes toward sex work. A dramatic recreation of a police sting which begins and ends the film takes place on a stroll that was at once a social space for trans women and a site of commerce. Such overlap would be familiar to the men of Rechy’s LA and the pair photographed by Seccombe in New York.

In light of that, it’s fair to say that these categories are historically overlapping—between gay men’s street cruising and hustling, trans sociality, and sex work. That’s partly because some of these identity categories were still being worked out, and partly because they happened in the same places at the same time. Gay sexual cultures, gender nonconformity, and sex work have been practiced in the same places and sometimes by the same people for a long time. These connections would not have needed explanation to nineteenth-century British mollies or rouged-up bar-cruising Weimar youths. And Seccombe, Preston, Rechy, and the women of Vestida de Azul show that this—for lack of a better word—blurriness persisted well into the second half of the twentieth century, throughout the 1960s, 70s, and 80s.

After the launch of Park Cruising in Montreal in May, I got to speaking with Sandra Wesley, the executive director of Stella, an organization run by and for sex workers. I remarked on the blurriness between the circuits I describe in Park Cruising and sex work. Wesley was quick to note an additional point: there have been significant trade-offs which have come with greater specificity of language.

On the one hand, Wesley told me, it has been important for sex workers to form affinity groups—to identify as sex workers and to identify sex work as work—to fight for better working conditions and legal reform. Greater categorical specificity draws people in, but it also casts people out. When you identify with greater specificity who is a sex worker (or a gay man, or a trans person) then you also create a class of people who are not that, not sex workers, not gay, not trans. You also risk being misunderstood by an audience ready to erase more informal types of sex work that aren’t happening in neat business-like interactions, or even lead some people to think that the movement for sex worker rights is about professionalizing sex work.

Lots of folks hold multiple identities as queer and trans people and sex workers, of course. Today, queer women and trans people are vastly overrepresented among sex workers. And men and nonbinary sex work was recently given a large and loving spotlight by the Gay Men’s Sexual Health Alliance in their “campaign.

This Pride, I invite Anansi readers to dwell on in these areas of overlap. The queer and trans political project has always included sex work as deeply, inextricably a part of the project toward sexual liberation. At times in this country, it has been sex workers and not the queer and trans community that has been at the vanguard of efforts to expand our rights. And the queer and trans community have sometimes been a fickle friend.

This is an important moment for working together. In October 2022, the Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform argued that a cluster of anti–sex work provisions in the Criminal Code are unconstitutional (full disclosure: I represented an intervenor in that case). These laws were introduced by Stephen Harper after three important provisions pertaining to sex work were struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2013. And they’ve been defended in court by Justin Trudeau’s government, despite earlier promises of repeal and review. The Alliance’s evidence highlights the most marginalized experiences, ones that don’t fit into the emerging stereotype of the entrepreneurial young woman empowered through sex work. They make the case that those with fewest options are most impacted by criminalization.

At the same time, there has been an enormous influx of interest and money into anti-trafficking programs in recent years. For example, in 2021, the Ontario government passed Bill 251 over the objections of sex work and queer advocacy groups. Federally, a bill is before Parliament which would broaden the circumstances which courts consider trafficking. Groups like Butterfly have pointed out that trafficking campaigns often amplify racist and anti-migrant sentiments, and lead to increases in state “surveillance, deportation, and detention” of migrant women. Programs targeting migrant and POC sex workers have now been enacted at all levels of government.

You can see efforts to divide—and efforts to reconnect—queer and trans activism with sex work in the debate over the Expungement of Historically Unjust Convictions Act. The provisions were introduced with much fanfare in 2017 to allow people to remove old convictions for buggery and anal sex from their criminal records. The law was so narrowly drafted that just nine of these expungements actually took place in the first three years of the program. The feds are now considering adding bawdy house convictions to the list—but not if sex work was involved. Thankfully, a group of queer historians are pointing out why that exclusion is a bad idea.

Our social histories are forever connected. Our political present is connected too, and the fight over unjust convictions is just one example. Given the onslaught of new cases, bills, and laws on sex work, it is incumbent on queer and trans people to pay attention, to speak out, and, for those of us with resources, to help.

During Pride Month, House of Anansi will be donating 10 percent of its website sales from houseofanansi.com to Montreal’s sex working organization, Stella. Learn more about Stella at https://chezstella.org/en/home/. Donations can also be made directly to Stella by going to donate: https://www.canadahelps.org/en/charities/stella-lamie-de-maimie/

Marcus McCann is a lawyer who has been involved in a number of high-profile cases about sex and state regulation. His latest book is Park Cruising: What Happens When We Wander Off the Path (House of Anansi, 2023), a book of essays affirming the positive value of sexuality and the ways that police, politicians, and park planners have responded to what people do in the bushes.